Effects-based scheduling for the OCaml compiler - w04

25 Jul 2025 • 5 min readNow that I have a working prototype of a linear self-scheduling OCaml compiler, the next step was to dispatch compilation tasks in parallel. My idea was to have some sort of process (domain?) pool to submit compilation tasks to, so I got that done fairly quickly:

type !'a promise

(** Type of a promise, representing an asynchronous return value that will

eventually be available. *)

val await : 'a promise -> 'a

(** [await p] blocks the calling domain until the promise [p] is resolved,

returning the value if it was resolved, or re-raising the wrapped exception

if it was rejected. *)

module Pool : sig

type t

(** Type of a thread pool. *)

val create : int -> t

(** [create n] creates a thread pool with [n] new domains. *)

val submit : t -> (unit -> 'a) -> 'a promise

(** [submit pool task] submits a task to be executed by the thread pool. *)

val join_and_shutdown : t -> unit

(** [join_and_shutdown pool] blocks the calling thread until all tasks are

finished, then closes the thread pool. *)

end

Internally, this is done with an array of Domain.t, and a thread-safe task queue (unit -> unit) TSQueue.t, which was nothing more than a wrapper around 'a Queue.t from stdlib. I have identical worker loops that sit on each domain, checking the queue for tasks when one completes.

Slight caveat: when a compilation task in the pool is waiting on another dependency to finish compiling, we certainly don’t want to block the entire domain that the task sits on. I needed some way to yield control back to the pool, allow other tasks to run on our domain, then continue the task at the point the task was suspended. (sounds familiar?) This was done with a list of continuations, each paired with a promise that signals the dependency’s completion. To suspend a task, I simply have it raise an effect.

Back to actual compiler work: David Allsopp (my supervisor!) suggested that for a first prototype of my parallel scheduler, I should start with Unix.create_process instead of jumping straight into domains, just to cut down on the mutable compiler global state that I would have to initially deal with. The idea was to only have the main process compile .ml files, and have it spawn child processes in parallel to compile missing .cmi interfaces; if those missing .cmi interfaces have their set of missing dependencies, they are compiled linearly1, i.e.: we block until its children are ready. The best way to explain this is with an example:

(* A.ml *)

let foo = 42

let () =

Printf.printf "foo: %d, bar: %s, sum(baz): %d\n"

foo (B.bar) (List.fold_left (+) 0 C.baz)

(* B.ml *)

let bar = "Hello, world!"

(* C.ml *)

let baz = [1; 2; 3; 4; 5]

(insert {A,B,C}.mli files as appropriate!)

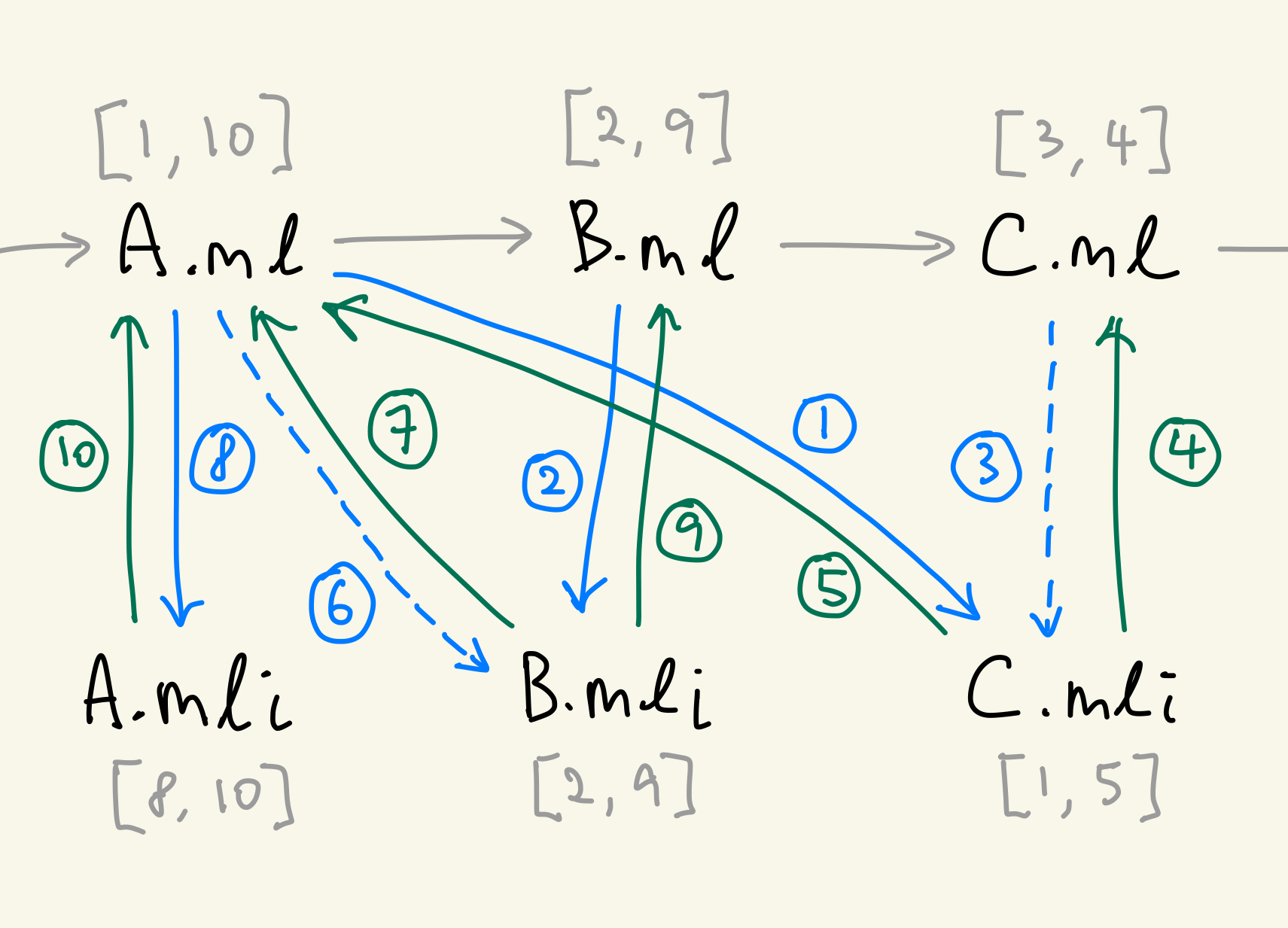

When we invoke our custom ocamlc to compile {A,B,C}.ml (in this order), what then should happen chronologically is:

A.mlstarts compiling. One of its dependenciesC.mliis missing, which is discovered by our effect handler after an effect is raised somewhere to locateC.mliin the load path. We launch a child process to compileC.mli, then move on immediately.B.mlstarts compiling. Its only dependencyB.mliis missing, so that gets compiled in parallel.C.mlstarts compiling. Its only dependencyC.mliis missing, but we already launched a child process to compile it (represented as a dotted line), so we attach the suspended compilation toC.cmiand resume it only when it is ready.- Suppose

C.cmiis now ready. We can now resume the compilation ofC.mland it should complete successfully, since that was our only dependency. A.mlwas also waiting onC.cmi, so it can also be resumed. It now hits a second missing dependencyB.mli, which we again compile in parallel.

Steps 6 to 10 follow the same logic, as shown in the diagram above. We fold on the list of implementations {A,B,C}.ml until all of them compile successfully. I had most of the code down for this by the end of week.

Finally, I took a couple of hours out of my weekend to make this website! I used Jekyll, a static site generator, which was surprisingly pleasant to set up and easy to work with. The source code is publicly available on GitHub.

-

This is actually non-trivial, since the main process wants to launch child processes in parallel, but the child processes want to be linear. I did this by temporarily maintaining two branches of the compiler, one for the main process itself (with all this new fancy parallelism) and one that the main process launches (with our linear compiler from the start of week). I take my existing compiler and install it to some directory, but instead of using its executables directly, I create a new entry point to replace

driver/main.mland link against the.cmafiles in the installation to create the parallel compiler. This also doubles as a hack for me to use theUnixmodule in the compiler, since that originally depended onocamlcto be built, which in turn depends onocamlcommon.cma, which likely contains whatever that I need to modify, and I can’t have those depend onUnix. ↩